CHIEFS

Kansas City, 1997

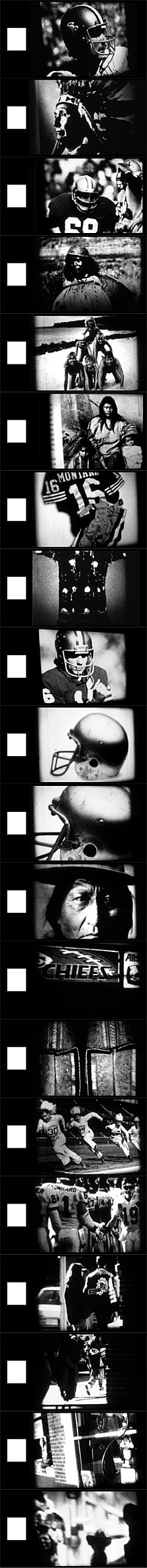

Super-8 for a Kansas City audience, b/w, 3 min.

During a stay of a few months in this city, I noticed the general populous' obsession with its football team, the "Chiefs". How could I have missed it: it was in fact impossible to escape the sports team's ubiquitous logo. It was in shop windows, bumper-stickers -- people were literally draping themselves in it, the logo appearing on shoes, pants, shirts, and jackets everywhere. The acceptable (desirable!) business attire was a normal business suit, complemented with a colorful yellow, red, and white "CHIEFS" jacket on top. The logo, by the way, is a Disney-style cartoon caricature of a grinning "indian"*.

You will not likely hear about it in the mainstream press, but there is a debate quietly raging in the U.S. Or rather, the debate is hardly even a debate, since no one seems to care about the issue except the thousands of Native Americans occasionally protesting at sports events. There are many such sports teams that usurp Native American culture by naming their teams "Redskins", "Braves", "Chiefs", or even by directly taking the name of a tribe, such as "Seminoles" etc. It is scarcely necessary to explain the nature of the issue: it is clear that the appropriation of Native American culture and its transformation into a simple mascot, is demeaning, ignorant, racist, and profoundly ironic. It evokes the bloody history of the U.S. and the creation of a myth about that history, by "replaying" it as a sports game. It is interesting to note that, in an age of political correctness in the U.S., this issue has somehow managed to escape any significant reform. Perhaps this is because the very topic seems to be entirely taboo to the average American. It is perhaps none other than a collective suppression of the emotion that--if one were truly to face up to it--would mean acknowledging a virtually total physical and cultural genocide of the First Americans.

But in my eye, a real censorship of that sordid chapter in U.S. history is perhaps exactly this appropriation: it is a re-making of the "indian" as something existing exclusively for the naming sports teams (the same goes for animal mascots by the way), rather than a real culture that once thrived where white men now sit in traffic jams on freeway on-ramps. This re-making is worse than forgetfulness. Why is it that in the U.S. we never hear about "truth and reconciliation" regarding this issue? Rather, we hear only excuses, such as that the land was legally and fairly purchased (Uh, right. On this topic read Howard Zinn's "A People's History of the United States of America"), and that it's not the white man's fault if the "indian" didn't understand the concept of ownership of land, and other justifications.

As an expression of my surprise at the prevalence, blithe acceptance, and even proud "wearing" of this mascot, and the lack of discourse about the issue in Kansas City "culture", I decided to make a short film, comparing the representation of American football iconography to that of Native American culture. To do this, I leafed through books on these two subjects in parallel at the public library, and filmed my findings: both were represented in books as though in a kind of museum: noble portraits of the "protagonists", their articles of clothing and equipment laid out carefully for display. I saw such similar totemic iconography in books on both subjects, that I was able to find pairs of similar images and compare them through the medium of film. I then went out into the city and filmed what evidence I could find of both cultures: such as a Jeep "Cherokee", a window display of a frontier style railway, people dressed as "Chiefs" fans...

The film was shown to a Kansas City audience of about 150 people, during a film festival (The Bentley Super-8 festival).

Incidentally, in order to submit the film within the deadline, I went to the house of the director of the festival. He greeted me at the door with a "Chiefs" baseball hat, the "grinning indian" on his hat grinning at me as I handed him the reel of film.

Another remarkable footnote: a famous American football star, Joe Montana, and his family happened to make up a part of the iconography used in the film, since they were the subject of the "revered" idolatry presented in one of the books I found. The depiction of him as "warrior", with his "tribe" (family or fellow football players) was an integral part of the parallel I found with the presentation of the family life and artifacts of Native American tribes. Strangely, a few months after the screening of the film in Kansas City, I met Joe Montana purely by chance at the Guggenheim museum in Venice, where I was on an internship. I would never have recognized him, but some astute art-interns/football-fans noticed him in the sculpture garden and were running around the museum whispering "it's Joe Montana!!" I walked up and greeted him, and got a rather icy response. I decided on the spot that I was not going to tell him about his unwitting participation in my film, for fear of a legal problem. Too bad, for it would have been exactly the person I would have liked to engage in a discussion on the topic, since through his whole career he was entwined in the football myth and in a way with the mascot debacle, since he gained his monumental fame during his time as one of the Kansas City "CHIEFS". I fumbled.

*Update: The grinning indian is now nowhere to be found on the website of the Kansas City Chiefs football team! I must surmise that things may have indeed changed for the better in the last 10 years. Alas, the present logo is an arrow-head, and the name is still, of course, the "Chiefs".